COLOMBO, Sri Lanka – As Sri Lanka faces its worst-ever economic crisis, a project kickstarted by Better Work-partner company Hela Apparel Holdings is providing a crucial lifeline to its garment workers.

Nishadi Kaushalya Fernando embroiders a cloth using a cross-stitch technique in her home in the village of Boyagne, in central Sri Lanka. Nishadi works as a coordinator of the engineering department at Hela Apparel Holdings—Narammala. She is her family’s breadwinner. As the economic crisis hit the country, her salary suddenly became insufficient to cover her family’s basic needs, so she started her own business.

Family photos are displayed in Nishadi’s family home, which she shares with her mother and two younger brothers. She says that since starting her business, her family’s support has allowed her to concentrate on her cross-stitch work when at home.

Nishadi cross-stitches a cloth she will later sell at the markets of the factory branch where she works. Nishadi says she has faced many challenges. Power cuts often affect her area, leaving her home without electricity. In these cases, she stays at the factory after work to catch up on her cross-stitching.

Nishadi stands in front of her home, showing one of her cross-stitch creations. She says her dream was to build a house where she could live happily with her mother and brothers. When it comes to her business, she would like to export her products one day. Nishadi also has a Facebook page called “Kaushy Crafts,” where she has 1,600 followers and through which she has already received 25 orders.

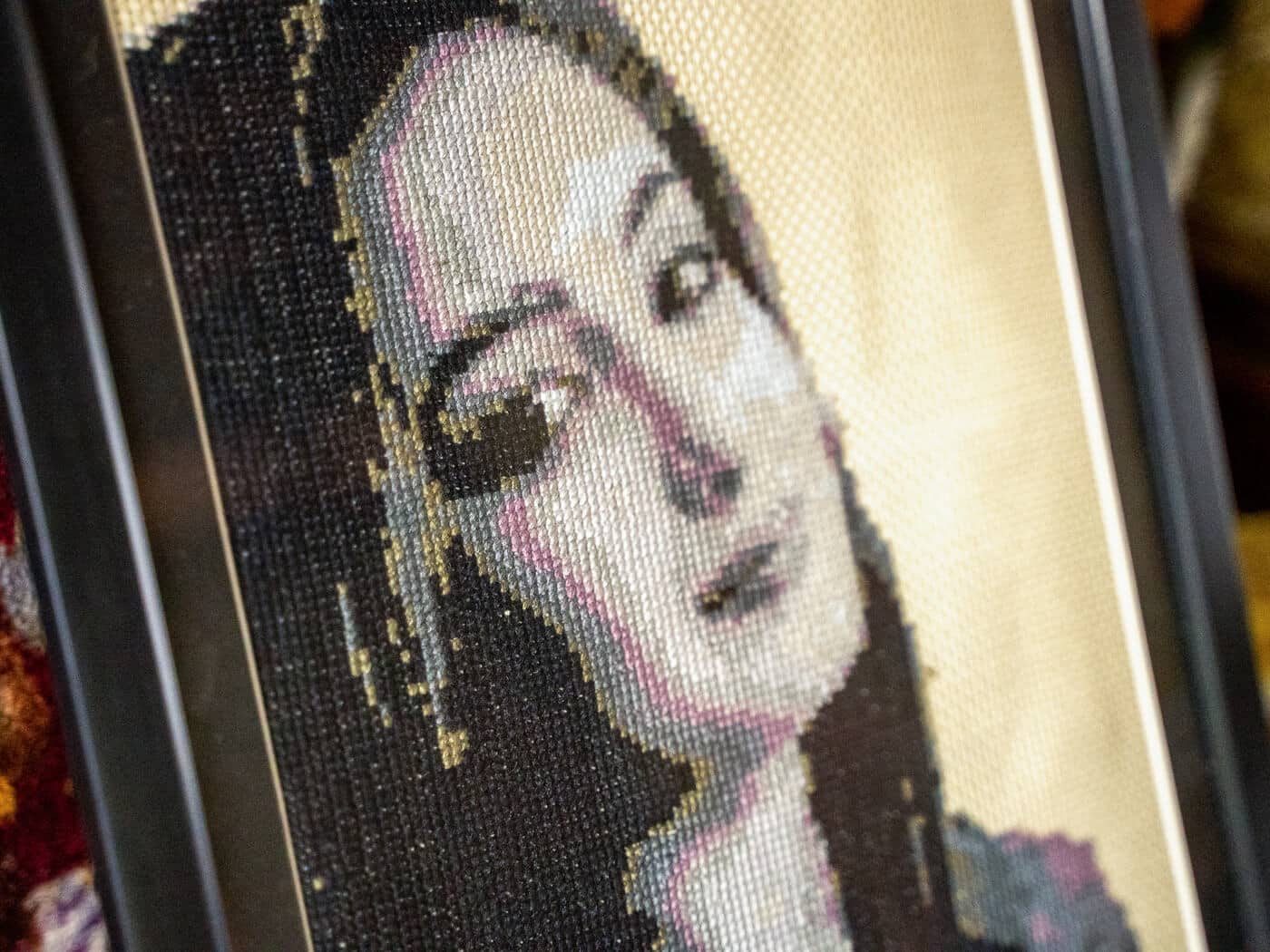

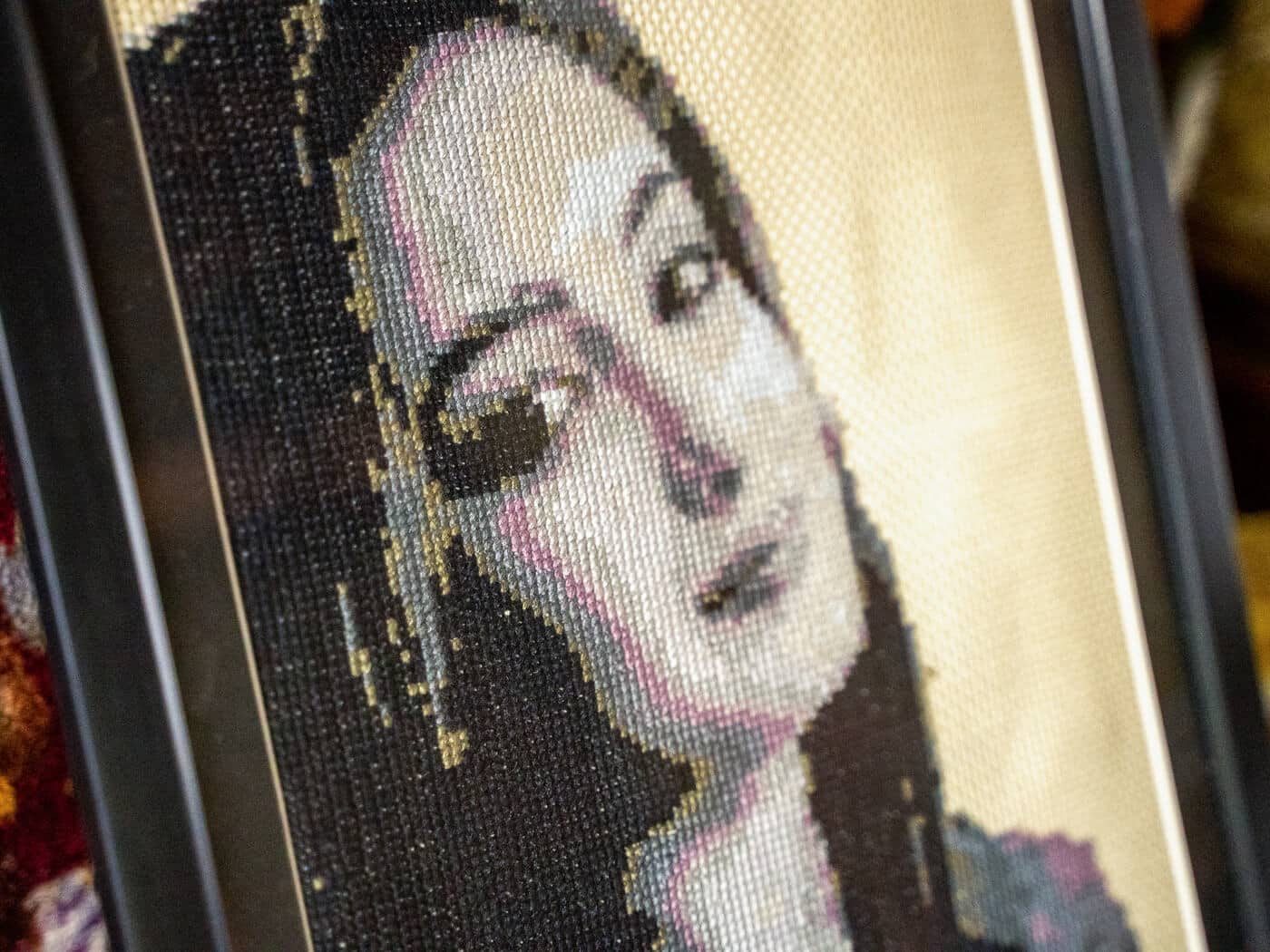

One of Nishadi’s cross-stitching creations. Nishadi says one of the company’s HR executives introduced her to the Diriliya project. “She encouraged me to display a couple of my cross-stitching samples at the Hela Pola market and, with that, my business took off,” Nishadi says. Her early cross-stich designs were mostly simple landscapes. She initially learned how to cross stitch at school during home science class and has kept doing it as a hobby ever since.

Nishadi has been training her cousin Saumya Dewangani to help her with the cross-stitching production to expand her business. “I already gave her two of my newest orders and I am closely monitoring her work,” Nishadi says. “There have been instances where I thought of giving up, but the training I recently received on how to emerge from a crisis, has given me further motivation to keep my business running.”

Nishadi sits at the monthly Hela Pola market. Here, customers have the chance to purchase her crafts and the products of her colleagues. She says the sale of one of her elaborate cross stitch products would equal half of her monthly salary. New entrepreneurs also have the opportunity to expand their network of business contacts. Her work is displayed at Sri Lanka Labour Ministry and dons the houses of Sri Lankan cricketer, actors, and musicians.

Lalith De Silva, 52, works with his brother on a coconut shell product in his workshop in the town of Horana, in Western Sri Lanka. He works in the cutting department of Hela Apparel Holdings—Balapokuna. He established his business in his free time, collaborating on the coconut shell production with his brother. Lalith initially sold his products on the side of the road, but sales drastically dropped following the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdown. He joined Diriliya after being scouted by the company’s HR officers and started selling his products at the factory’s monthly Hela Diriliya Pola market.

Lalith carries a tea set he produced from coconut shells in the garden of his home in western Sri Lanka. He says it has been hard to determine the prices for his products, as they are the result of a labour-intensive job. Spoons are his cheapest objects, selling for 60LKR (US$ 0.17), while a full tea set costs 9,000LKR (US$ 25), his most expensive product. Lalith has had strong demand for his goods and notes he is constantly looking to improve his production and reach out to a larger market. “I want this to become an international business and develop into a well-established online shop.”

At his home, Lalith displays his range of coconut shell products. Lalith once sold his products in a local supermarket chain, making about 70,000LKR (US$ 193) within a couple of hours. “It is not just about the sale I made on a given day – this experience was especially helpful for expanding my business contacts,” he says.

Lalith shows a detail of one of his products in his workshop. “I am very proud to say that one of my products was given as a gift to one of the most famous cricket players in Sri Lanka.” Adding that he has learned a lot from his customers and their feedback, Lalith says “I am not afraid of challenges. There could be raw material shortages, machine glitches, and capital challenges but I am ready to face all these issues.”

Loading his products with the help of his family onto their three-wheeled tuk-tuk, Lalith says the economic crisis has severely affected his family. His family was an essential source of motivation and support to keep his coconut shell product business running. “My family is everything. They have supported me throughout this new endeavour. My child helps me load and unload my products, and my wife’s encouragement is what I value most,” Lalith says.

Lalith shows a customer one of his products at his local, monthly Diriya Pola market. People visiting the venue often ask for his contact details to place additional orders. “With the extra income I have earned, I managed to enrol my son into a better school. My life goal is to provide him with the best education available in the country,” he says.

Employee-entrepreneurs are seen displaying their products at one of the Hela Apparel Holdings’ market venues in Sri Lanka. Each of the group’s six clothing plants in the country has its own market, a focal point in charge of the Diriliya activities and the different programme’s trainings and support available on site.

“If we look at the impact the Diriliya project has had on our workforce, we see that it has been a lifeline at a time of crisis,” says Hela Clothing Adviser for Group Management Committee Udena Wickremesooriya. “Workers were extremely happy in taking part in the project and develop their own businesses that, in many cases, has led them to establish working partnerships with their families. Some have even gone beyond that, employing a few people to help them with their newly established business.”

Priyantha Weerasinghe carves a new product out of a coconut shell in his workshop in the town of Ganewatta, in western Sri Lanka. He has been working as a mechanic at a branch of Hela Apparel Holdings for the past nine years and producing wooden objects for his homes in his spare time. “One day I showed my products to the HR officers who then immediately recruited me for the company’s Diriliya project,” he says. “Before that moment, I never believed I could have possibly made a business out of it.”

A traditional Sri Lankan Mask in Priyantha’s workshop in the town of Ganewetta in western Sri Lanka. Priyantha started working with bamboo, producing pens and phone holders. He later went on to expand his production to woodwork, creating food trays, traditional masks and other ornaments.

Showcasing one of his products, Priyantha says the ongoing crisis has severely affected his production, as the price of raw materials doubled within a few weeks. “I couldn’t sell the final products I created at the initially committed price, causing some discussions with my clients.”

Priyantha cuts pieces of wood in his temporary workshop, which he built next to his house “My dream is to have a separate working space with a workshop and a retail sale space one day. I am also hoping to buy a vehicle with the income I will earn from this business,” he says.

Standing in front of his house with his wife and one of his children, Priyantha holds a bag and some rush his wife will turn into baskets, floor mats and more bags. “I am encouraging my wife to also start her own business,” Priyantha says. “She just started weaving rush and reed, and I am looking forward to seeing her attend the Diriliya Rush and Reed training, so that she can learn new techniques.”

Mangalika Kumary, 40, is seen in the kitchen of her home in the town of Nawagamuwa, east of Colombo. She is a machine operator at a branch of Hela Apparel Holdings in Sri Lanka. The mother of four says her family could not afford to provide her with a high-level education. She started working at 14 years old, making ornaments out of ribbons and selling them to her friends. Thanks to her job, she says they have still managed to eat three meals a day despite the harsh crisis affecting the country.

Mangalika developed a charcoal-fuelled cooker with an electric flame controller with her son. “We have been facing LP gas [cooking fuel] shortages recently, which has made it difficult for me to prepare meals, especially in the morning,” she says. “My son suggested developing a new cooker together. After seeing the benefits of using it, I thought other mothers might face the same challenges. So, I decided to start manufacturing these cookers.”

Mangalika’s cooker, as seen in the kitchen of her home in Sri Lanka. Thanks to her participation in the Diriliya training, Mangalika was able to make more than 250,000LKR (US$ 700) within a few months. “I managed to save 90,000LKR (US$ 250) from the total amount for the education of my third son.”

Standing with her family in front of their home, Mangalika notes “My family is my strength; I wake up at 4am to finish all the housework before heading to the bus stop to catch the company bus to the factory at 6:20am. The series of trainings I have received from Diriliya helped me think differently and manage my finances better.”

Mangalika and her colleagues showcase their products while waiting for customers at the monthly Hela Pola market. Mangalika says she has been thrilled by the revenues she managed to earn through the selling of her electric cookers so far. “Much of the money I am gaining now will be used for my children’s’ education in the future. Still, completing the construction of our house is also among our top priorities at the moment.”

What has the Diriliya experience meant for workers?

“The country is going through a tough situation,” says Head of Better Work Sri Lanka Programme Kesava Murali. “The apparel sector has been crucial for the country’s economy throughout this time as it is Sri Lanka’s largest exporting industry and a major source of much needed foreign currency. It has also provided its workers with a stable job at a difficult time. But with Diriliya we are focusing on skills development and jobs creation for the workforce in the sector, fostering resilience in times of crises.”

Sri Lanka has faced severe challenges over the past few years. The 2019 Sri Lanka Easter bombings across several cities were followed by the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The ensuing negative impact was further exacerbated by the economic crisis that engulfed the country starting in 2019.

Shortage of foreign currency, spiralling inflation, rising costs, shortage of food, fuel, medicine and electricity have made the life of Sri Lankans extremely hard. The Diriliya project helped provide an additional income and psychological support to the workers and their families through the provision of financial and social stability.

Through Diriliya, the company’s workers are equipped with vocational training and targeted resources based on each of their projects as well as the technical, legal and financial know-how to establish their businesses. Their family members often join them in attending the courses and eventually set up a new family business together.

Attendees are supported to work on their entrepreneurial mindset, while being given the knowledge to start a business from scratch, including the development of a business model. They are eventually offered a platform to sell their products at the Hela Diriya Pola ” a factory-based marketplace. Manufacturing spans bamboo household goods, food, needle work, dress making and pottery, among others.

Participants are earning between 50-65 percent of their monthly wage thanks to their new businesses, a result that is making a clear impact on their lives and their families.

Why is the Diriliya programme so crucial now?

The minimum monthly wage for workers in Sri Lanka is 16,500 Sri Lankan Rupees (around US$ 45), while the average monthly salary for garment workers is 35,000 Sri Lankan Rupees (around US$ 95). Such payments are proving challenging amid the currency’s stark depreciation. Workers are faced with hard choices. For instance, in families with more than one child, parents are often forced to decide who they send to school.

Sri Lanka’s cost of food in December 2022 rose 64 percent from a year earlier. Cooking gas cylinder prices have almost quadrupled since the beginning of the crisis shooting up from some US$3.4 to about US$12—an increase of around 350%.

A World Food Programme (WFP) survey indicates 86 percent of families in Sri Lanka are resorting to at least one coping mechanism, including eating less, eating less nutritious food and skipping meals altogether.

This has triggered a vast exodus of local professionals relocating to the European Union, the U.S. and Australia.

“Sri Lanka’s brain drain has been going on for the past 30 years. However, the rate of migration we are seeing today is unprecedented,” says Hela Clothing Adviser for Group Management Committee Udena Wickremesooriya. “But apparel workers don’t have the qualifications nor the economic means to leave the country. They are the ones who are remaining and need to be taken care of as they lack any other options.”

Based on its 30-years of experience in the garment sector, Hela Apparel Holdings has grown to employ about 20,000 people across Sri Lanka, Egypt and Ethiopia, of whom 8,500 are based in the island nation. Female employees make up three quarters of the overall workforce.

“Sri Lankans are risk takers. Most of our economy is run by women, either being employed in the local apparel and tea industries or as migrant workers,” Wickremesooriya says. “This project was initially thought to help generate additional income. But when the crisis hit, it became even more meaningful and relevant to the workforce, the company and the country”.

Better Work Sri Lanka’s Murali agrees, stressing on the fact that Diriliya is a great practice that is temporarily helping workers and their families cope with the ongoing economic downturn. Better Work would like to use the Hela model and expand it at a national level through its network of factories, eventually transforming it into a national capacity-building programme in collaboration with the Labour Ministry.

“We see this initiative as potentially leading workers to manage an entrepreneurial activity with their family members in the long run,” Murali says. “We would also like Diriliya to become an instrument through which the workforce could get financial support at zero interest through their factories, using their income as a guarantee, since access to finance is currently a major problem for many.”